The Kingdom of the Happy Land - Part 2

To get someone’s attention, just say, “Here’s what happened ….,” and then tell the story

I’ve read that getting people’s attention is now more profitable than providing them with information. Laura Marsh wrote in The New York Review of Books,

The sheer amount of digital information has become a burden. Everyone labors under the strain of cheap, overwhelming information.

The scarcest thing now is getting people’s attention.

The mysterious Kingdom of the Happy Land got my attention years ago when Sam told me stories he had heard about it as a boy in Henderson County, NC. It was said that the remains of the legendary Kingdom, chimney stones and maybe the shell of a cabin, were to be found south of Lake Summit near the state line. His dad worked with and knew a few of the Kingdom’s descendants.

Ever since it got my attention a few years ago, I’ve wanted more information.

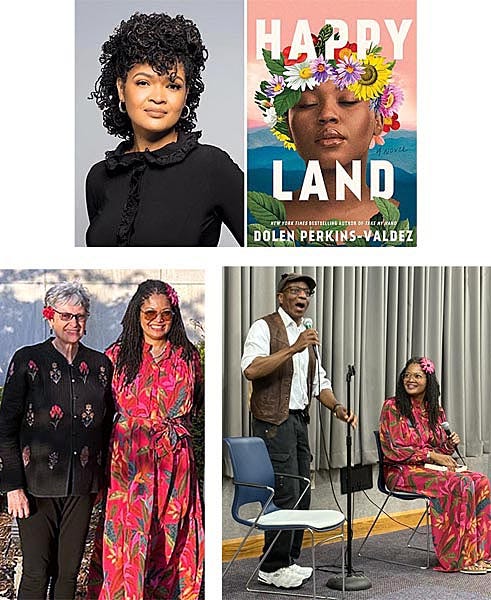

So, recently I went to the Hendersonville Library to hear Dolan Perkins-Valdez speak about her new novel, Happy Land. While writing the book, she wanted to learn the true story behind her subject and enlisted the help of local historian-librarian Ronnie Pepper and researcher Suzanne Hale.

I’ve finished reading Happy Land now and have been soaking up all the information I can about this small band of newly freed slaves. During Reconstruction in the 1860s, they created a community in a corner of Henderson County, worked for pay, and eventually bought land.

Perkins-Valdez had two goals in writing this book. She said,

I had heard about Black intentional communities, but not this one. What caught my attention was that they had named a king and queen and had imagined themselves as a kingdom.

So, I began to dig for information. First, I wanted to correct what had been assumed to be true for so long.

Second, I wanted to ask what it meant to these newly freed African Americans to be property owners in North Carolina in the 1870s and 1880s, symbolically, spiritually, and emotionally.

The main question in my book is, what happens when we lose our history? I hope people will be inspired to just ask their elders, while their elders are still here.

“First, I wanted to correct the legend”

The legend —

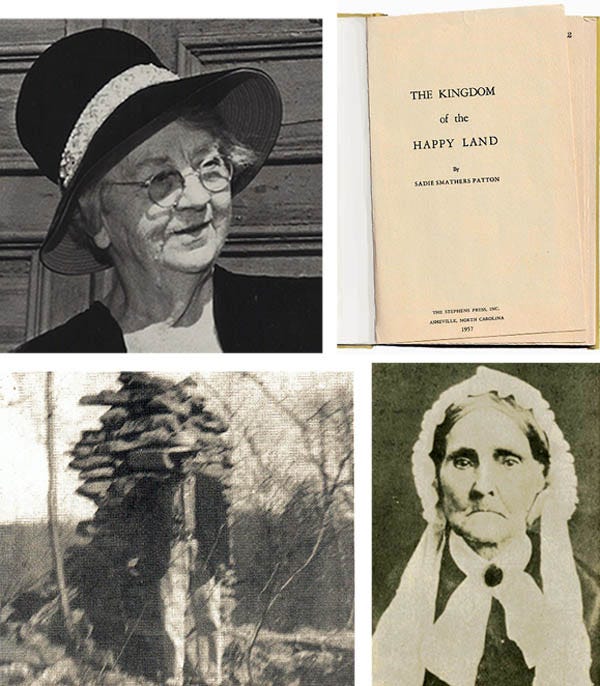

Sadie Patton’s 1957 pamphlet says that after the Civil War, “devastation and ruin” faced the newly-freed slaves — as, she added, it did their owners.

Left to “a fate worse than slavery — homeless, and now in bondage to want and fear” — a small group started walking from Mississippi and grew in size as they passed through Alabama and Georgia. Finally, they settled in North Carolina, “in a strange and primitive form of collectivism.”

Patton says their story can “only be pieced together from scraps of old traditions,” from legends and oral history. Recent research has shown some of these sources, including Patton’s pamphlet, are unreliable.

The reality —

In response to this legend, local historian Ronnie Pepper has said,

Patton’s pamphlet is in the library. But the story is told from a white standpoint, And it needs to be told from an African American perspective. A lot of the stories that we hear are told from a different perspective, and there’s a lot that’s missed. There’s room for balance, for both sides.

Pepper goes on to add the freed slave’s perspective to Patton’s piecing together of legends. He says,

Here is a group of people who were free, but weren’t yet educated about the law, paying taxes … Think about that, if they had to go pay the taxes and someone says, “Wait a minute. You can come in the courthouse? You own land? Hm-mm.” How hard would it be to get good answers if somebody didn’t want you there?

From the safety of the white-man’s culture after the Civil War, journalists scoffed at the efforts of newly freed slaves. You can see examples of this, as well as actual legal documents, on a website I learned about at the Perkins-Valdez library talk. Here are some of them:

The website says,

The articles [like the one on the left, above] lean into fear-based stereotypes of the time, depicting freedpeople as incapable of self-governance and prone to violence and moral corruption.

Second, what did it mean to these emancipated African Americans to be property owners?

During this time, the purpose of many of the Black “intentional communities” was assimilation into the free population. But it was a time of reactionary Ku Klux Klan violence, especially related to voting, and the Kingdom planners, with perhaps 200 others in their group, chose to leave South Carolina. They envisioned the peace and freedom of a secluded, self-supporting community under royal self-rule like the remembered kingdoms of Africa.

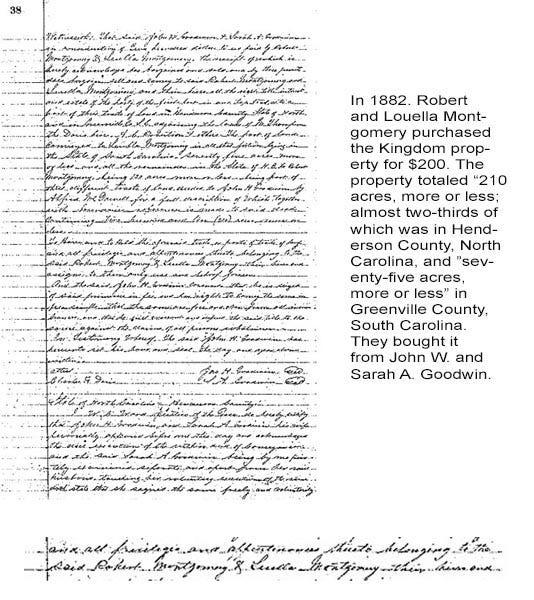

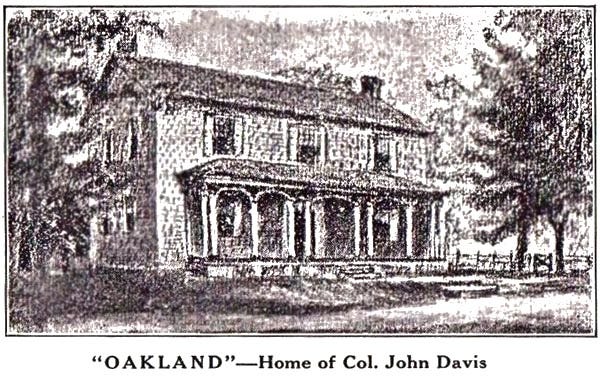

Arriving in North Carolina, they arranged to work for Serepta Davis, widow of John Davis. Of reduced means herself, Davis put them to work restoring Oakland, the inn she owned, in exchange for their living on her property.

The Kingdom people also subsistence-farmed, and made money in nearby towns, in transporting goods, in the zircon mines, and in making and selling Happy Land Liniment and, reportedly, a Balm of Gilead.

All the money was kept by the king who dispensed it, while also saving for the community’s future security. By 1882, they were able to buy land.

But this story is also about the emancipation of women. In Happy Land, Queen Louella calls together the women of the Kingdom. She says,

I inhaled and tried to quiet my nerves by saying, “Ladies".”

The word was a powerful one for us. Ladyhood had been a term reserved for white women. So when I said it, they heard it.

It was hard not to examine every word in these days of freedom … it was during freedom that we took back our words, starting with what we called ourselves.

Louella is given a seat at the men’s council. Later, she says,

I had brought more women onto the council. … The women now had equal say.

The author of Happy Land had a third goal for her book.

She spotlights the disappearance of the Kingdom after 1918, partly because the heirs had moved or lost their land to an unfair, powerful law.

This [loss] occurs when property is transferred to multiple family members as “tenants in common”, often without a will. This leaves the heirs without clear title and property is vulnerable to being sold to predatory developers.

In 2022, it was estimated that

the compounded value of the Black land loss from 1920 to 1997 is roughly $326 billion.

So, through her story about Louella (and her descendant Nikki), Perkins-Valdez also wants to raise awareness of the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act (UPHPA), which helps families understand their property rights.

In part, what does this story mean to us today?

Louella’s story (along with her descendant Nikki’s) is bigger than a long-ago moment in our nation’s history. It’s also about our vulnerability today as (what I will call) “Americans in common”.

In her April 22, 2025, Letter, Heather Cox Richardson quotes a senior lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin Law School:

[The Republican] Project 2025 is a “wish list” for the oil, gas, and mining industries and developers. It promotes … rolling back protections on federal lands, and selling off more land to private developers.

Now that I’ve read and thought about Happy Land for two weeks, I realize what first attracted me to the story of the Kingdom. It was more than its mystique of vanished royalty, and even more than its curious mix of oral history intensified by old records buried in courthouse files.

It was the word “happy”. Just, happy.

So interesting! Thanks

Deda, your writing today brought mixed emotions: joy that this settlement came into being after 21/2 centuries of enslavement, with so much sacrifice and work on the part of so many; hope inspired by those newly freed people who took a such a long journey on every front; happiness to hear about their dreams and efforts brought to reality; and sadness to realize that, yet again, those who wanted to defeat them took their advantage.

The Happy Land story is one of many we all learned in school, about emigrants here from China, Italy, Ireland, Russia, and more recently, from South America. Some stories have been about resilience and triumph. More recently, I’m feeling scared and hopeless. We all worked for a place here, seeking a better life. How can this latest group of immigrants be treated with so much hatred? I hope that we can see good coming sometime and soon.